The earliest recorded dispute involving the copying of a map involved one of the more colourful figures of Australian colonial history – Thomas Livingstone Mitchell. As fourth Surveyor General of NSW, Mitchell undertook a trigonometrical survey to produce a map he would later call the Map of the Nineteen Counties. The survey was in response to instructions from the King, who wanted an accurate map of New South Wales for the purpose of defining the boundaries of lots of land to be auctioned off to prospective settlers. After persuading Governor Darling that such a map would require a detailed trigonometrical survey, Mitchell worked on the Crown-commissioned survey from 1828–1834, and in doing so found himself in two notable disputes.

1. Dispute with the Colonial Office – 1834

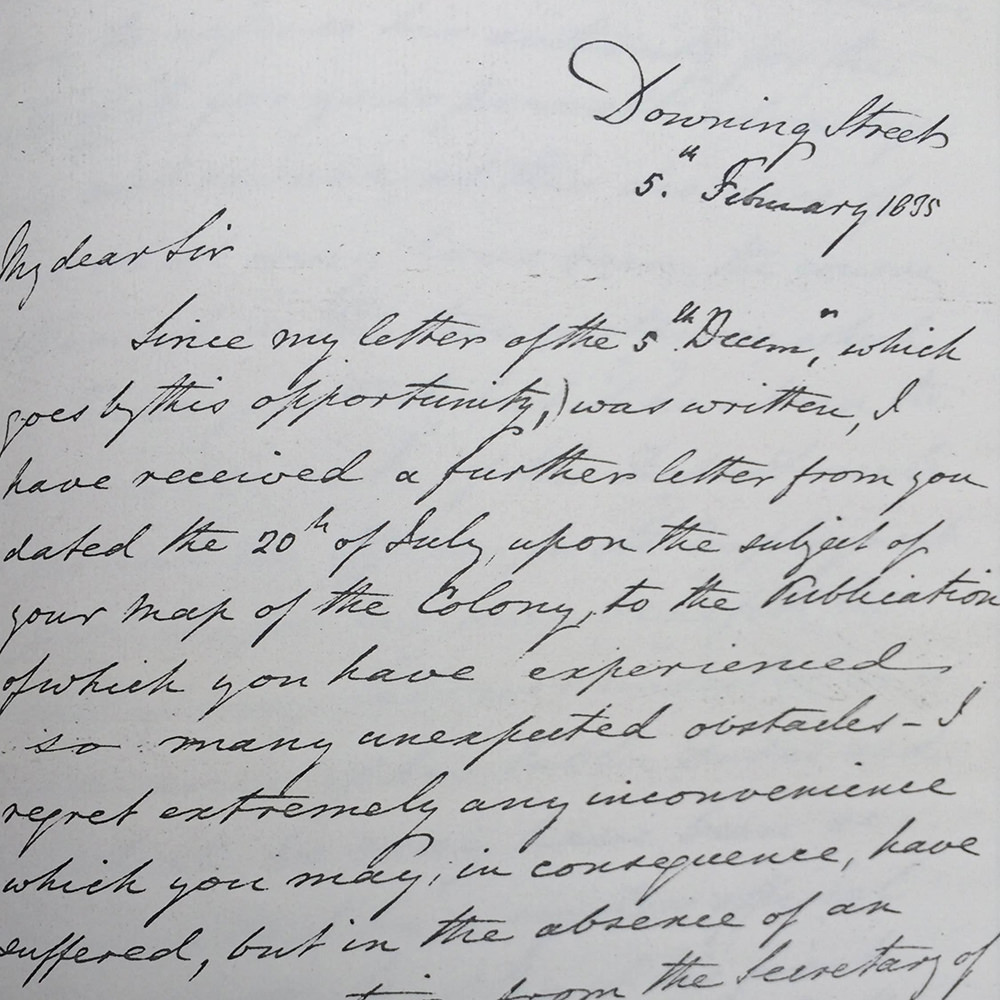

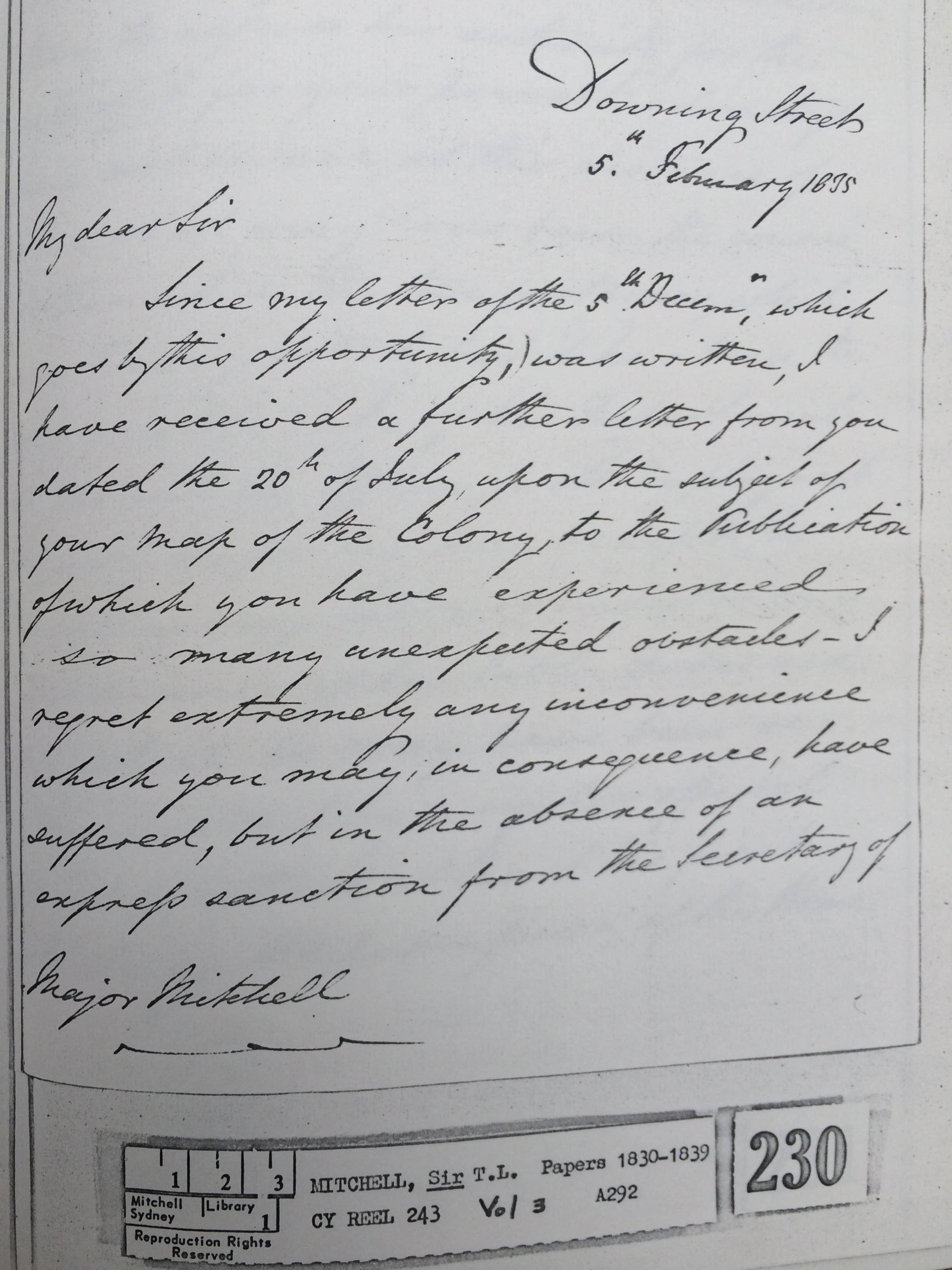

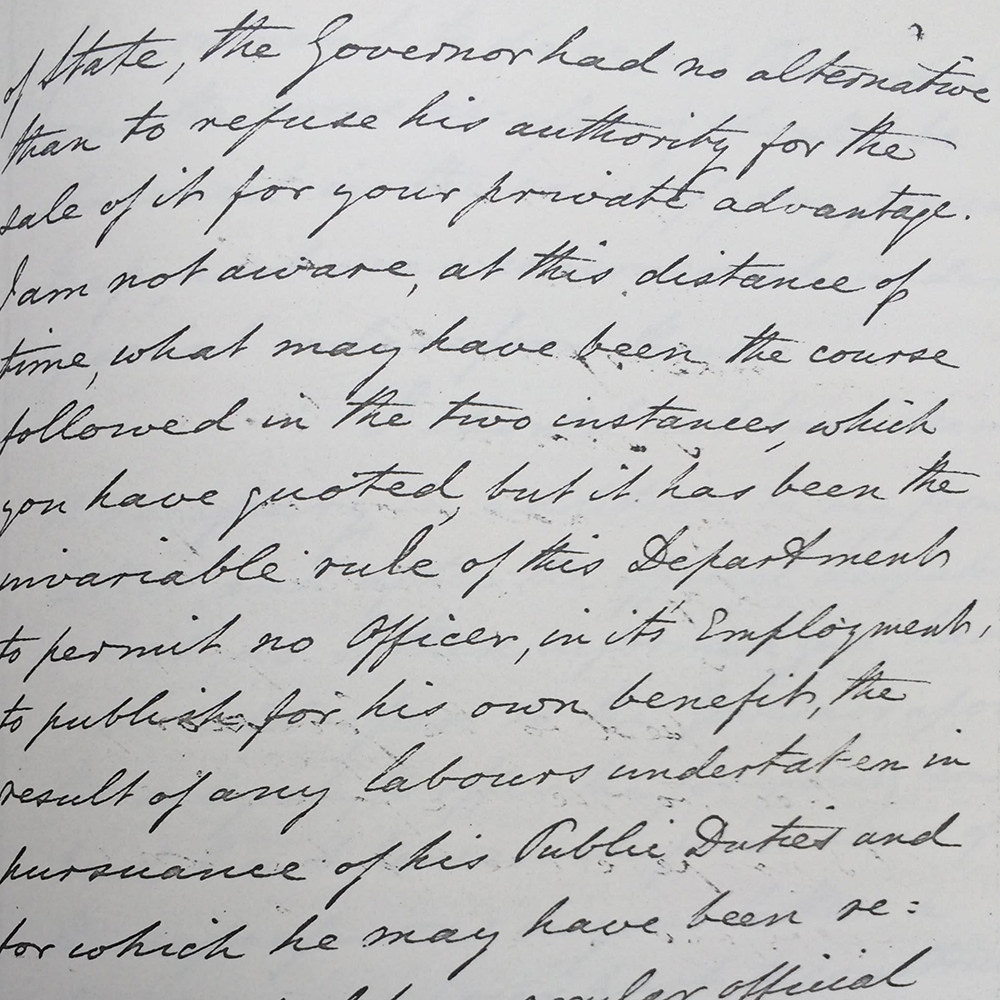

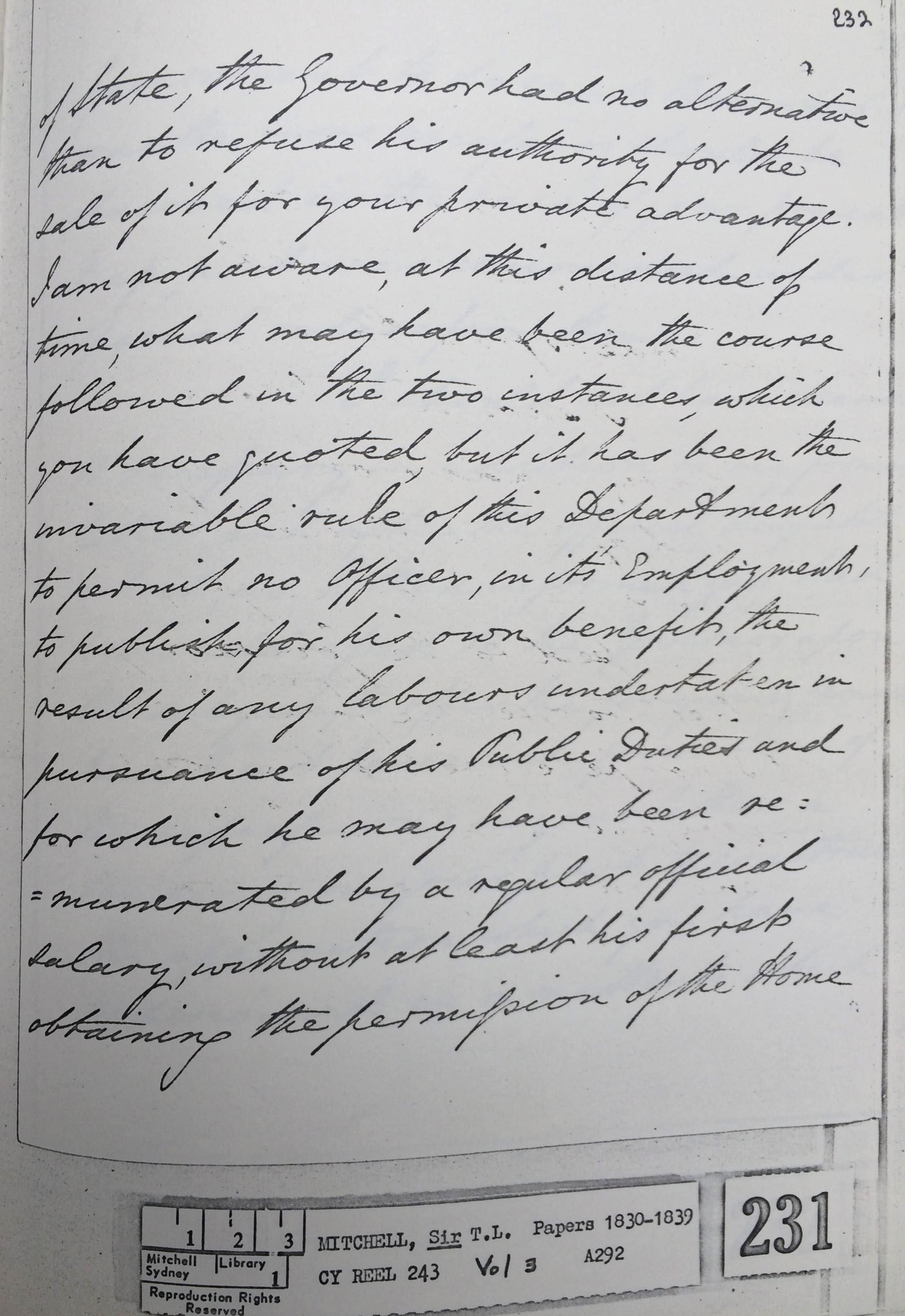

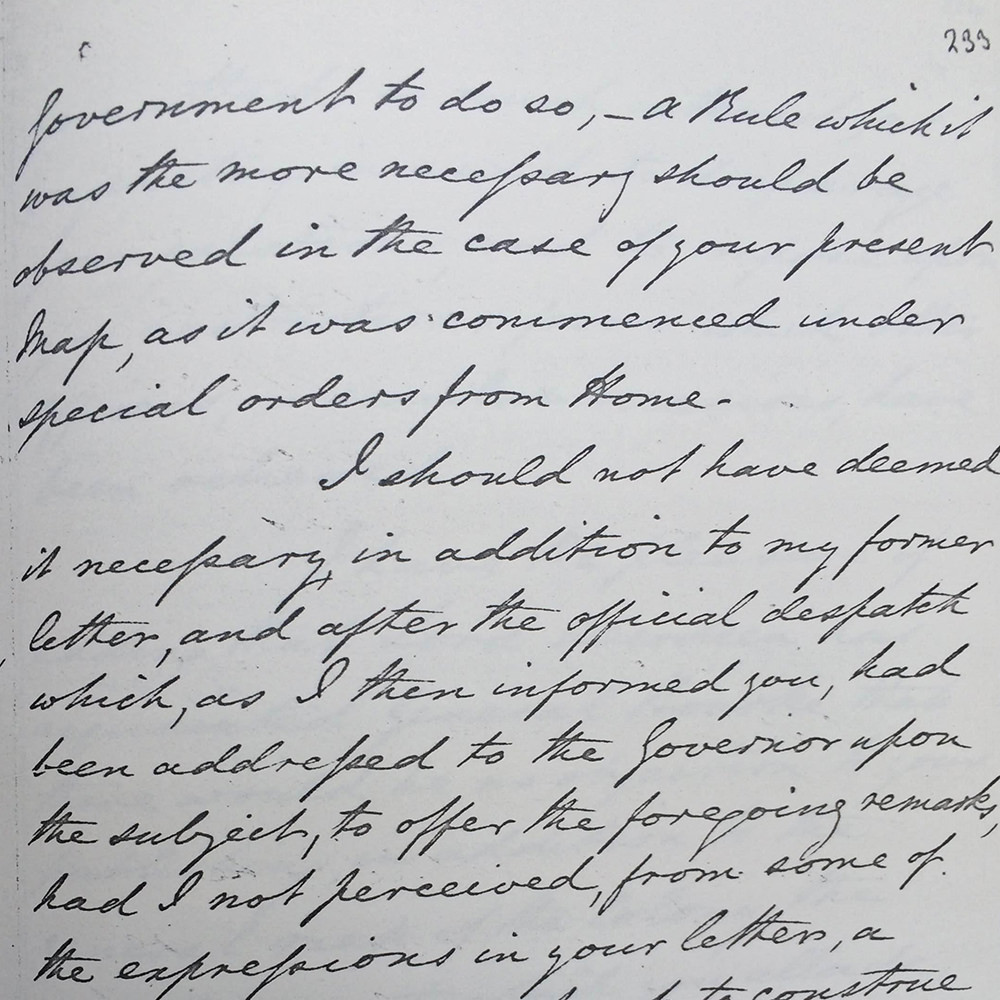

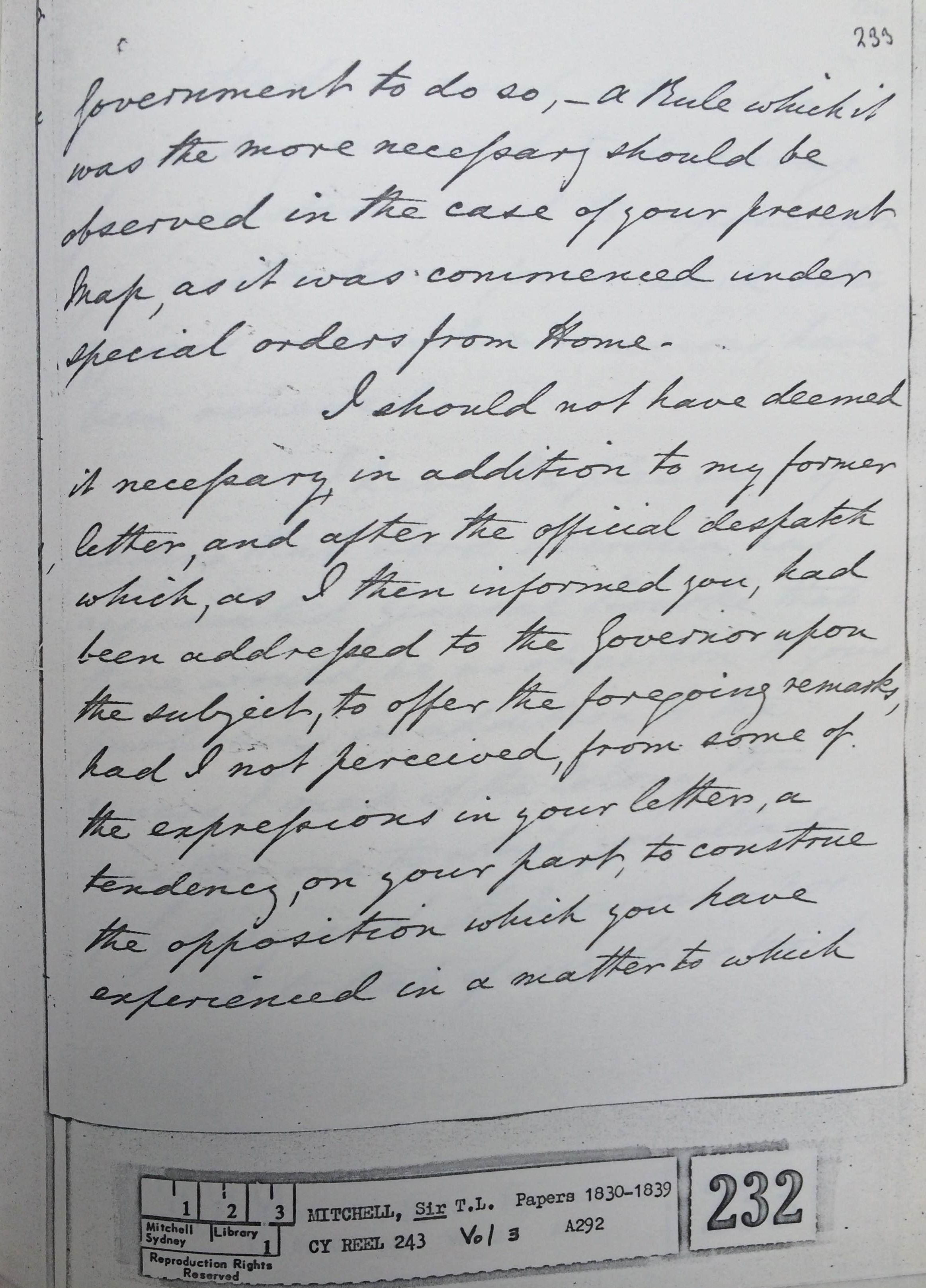

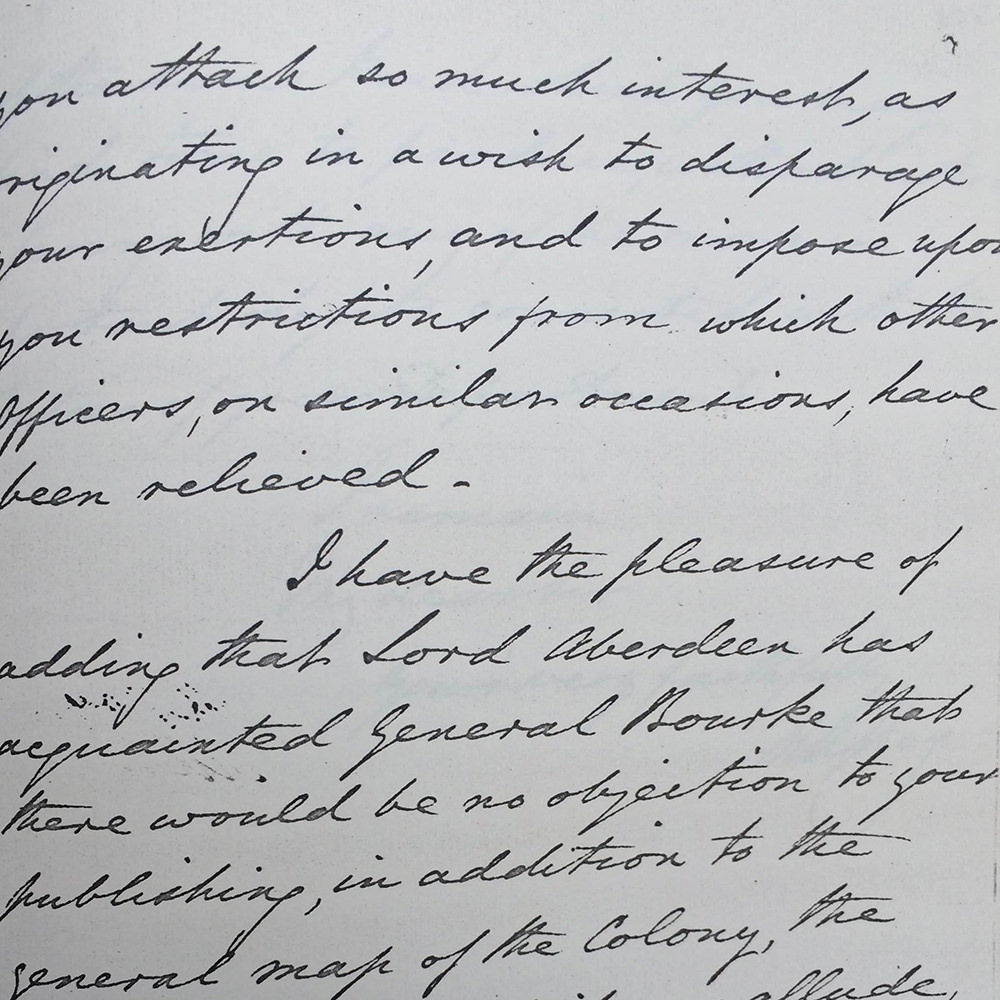

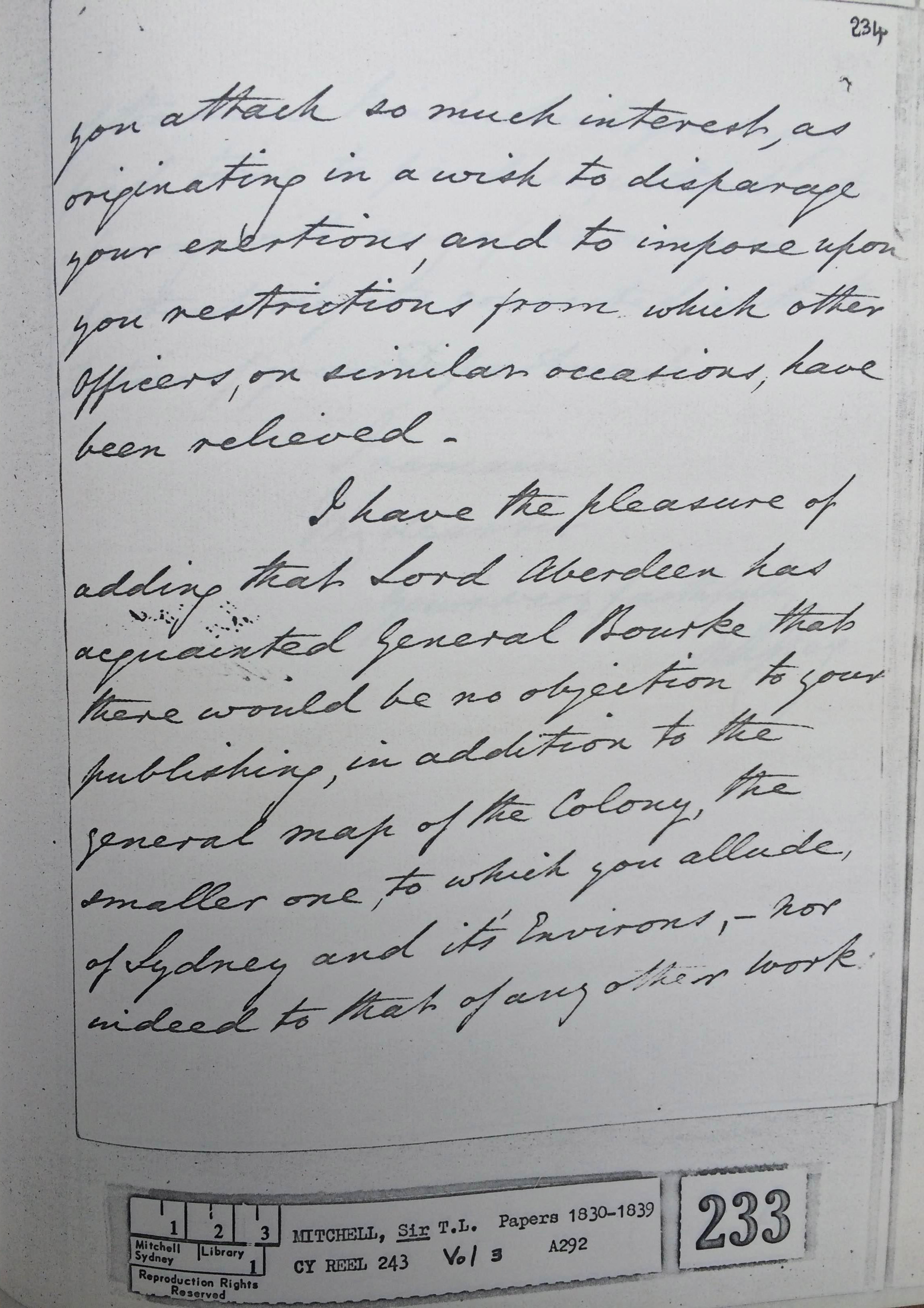

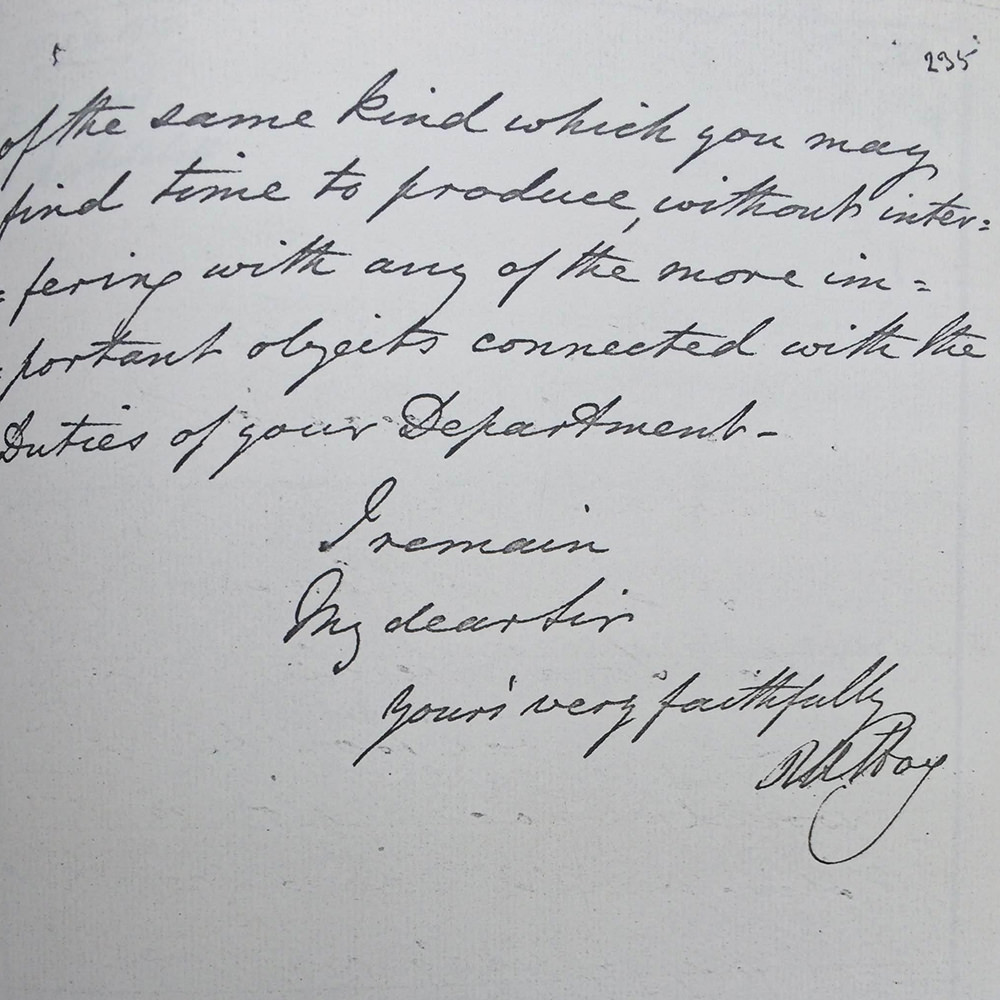

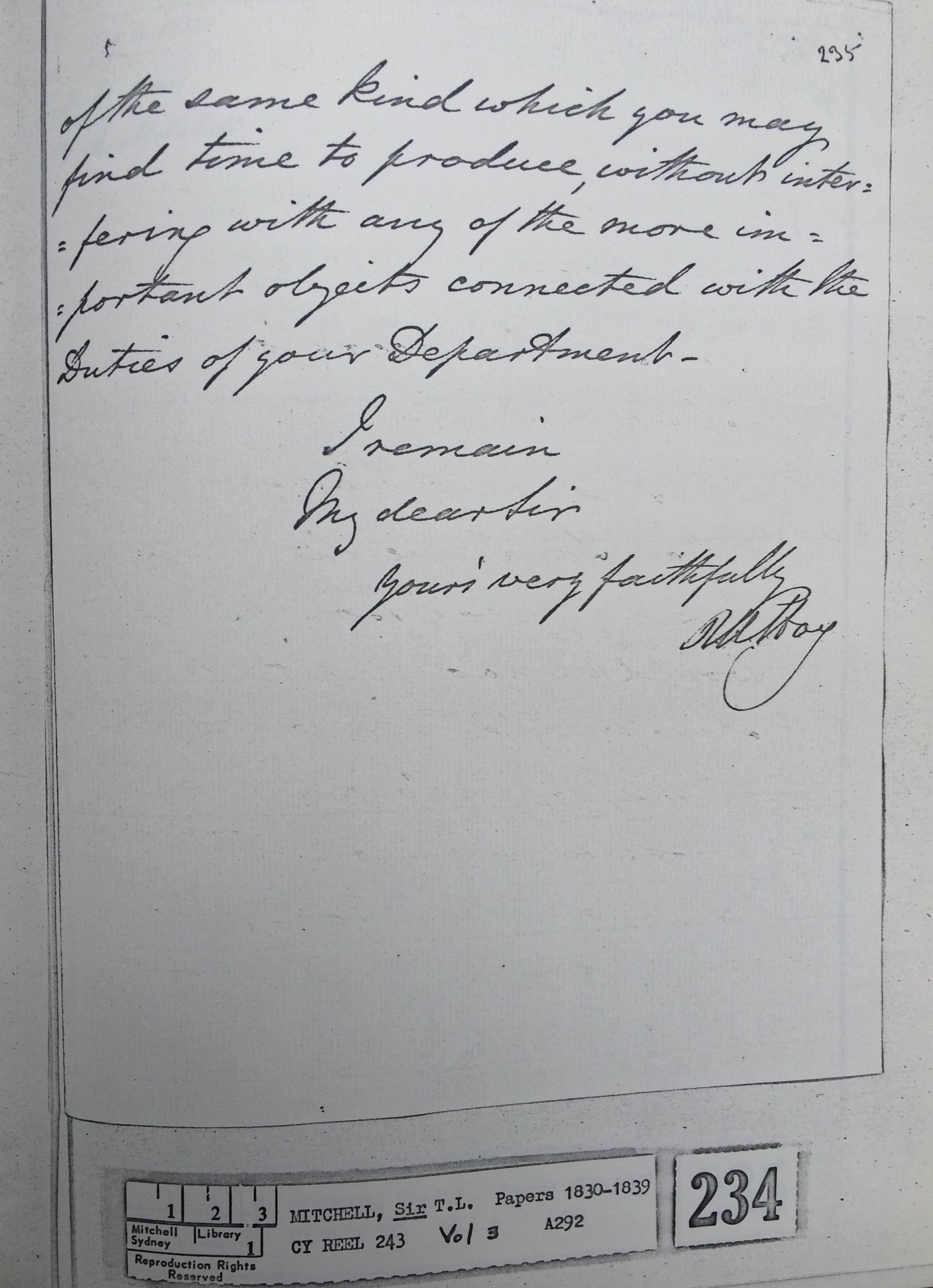

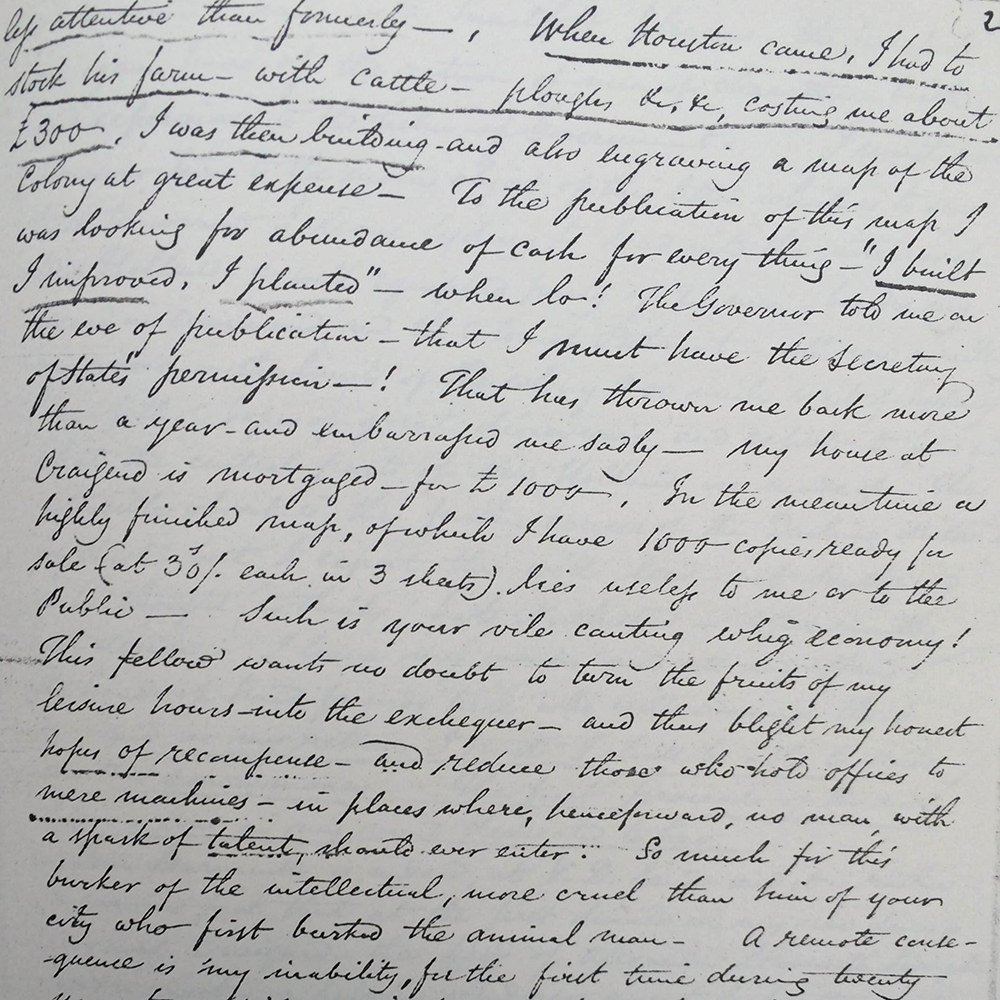

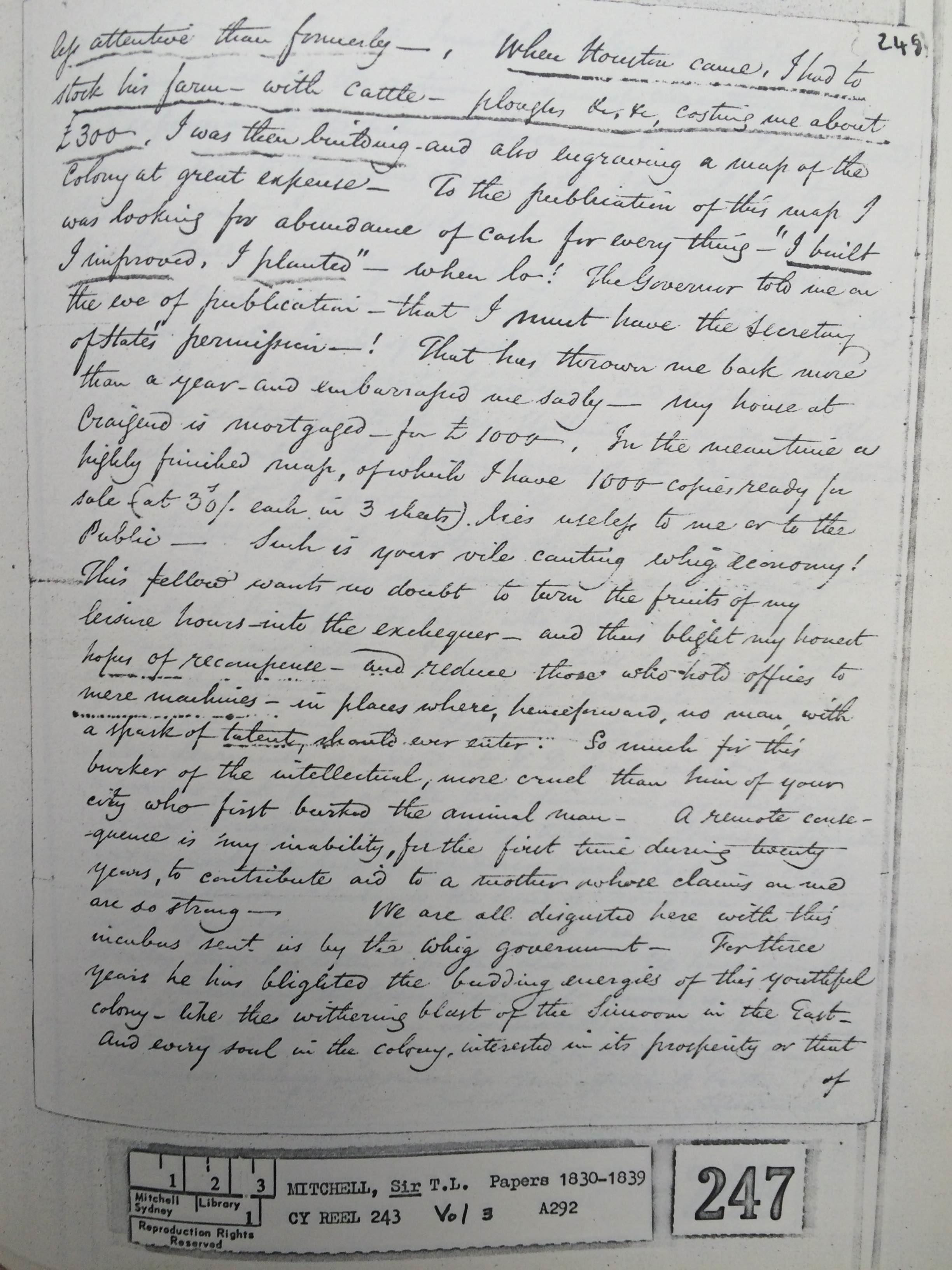

In an attempt to commercially exploit the ‘fruits of his labour’, in 1834 Mitchell sought permission from Darling’s successor, Governor Bourke, to privately print two hundred copies of the map he had produced from the surveys so that he could sell them in Sydney and in London. Drafting, engraving and printing the map had personally cost Mitchell 900 pounds and he wanted to recoup his expenses. Bourke refused to allow Mitchell to publish copies of the map without the express permission of the Secretary of State, Edward Stanley. When pressed by Mitchell, Under-secretary Robert Hay pointed to an apparent rule in the Colonial Office forbidding public servants from profiting from works undertaken in the course of their public duties. Mitchell eventually received permission in December 1834 from the acting Secretary of State, the Duke of Wellington, who approved the purchase of 200 copies of Mitchell’s maps at one pound each.

While Mitchell does not explicitly refer to copyright law in his correspondence, he was clearly concerned to stop unauthorised publication of his maps. In 1834, he wrote to Governor Bourke’s private secretary:

How the publication may remunerate me is uncertain, but the production of a work of permanent utility, has been my chief object; and all I have to ask of the Government is, that no person may be permitted to publish from the copy of my map, now sent hence, any map likely to affect the sale of those copies thereof which I am preparing to send home for publication and sale.

The Duke of Wellington, when acceding to Mitchell’s request, noted that ‘care will be taken that the object […] is not defeated by permitting any part of its contents to be pirated by any printer or publisher of maps in this Country’.

In this context, it is interesting to note the publication line. In Britain, the Engravings Acts required insertion of the name of the print’s proprietor on each print in order to claim the protection of the Act. By including this statement, Mitchell reveals he is aware of copyright’s legislative requirements. Although it is unlikely copyright would apply to a map first published in New South Wales, the inclusion of the (probably false) statement ‘Republished in London’ might have been enough to deter potential pirates.

2. Dispute with Dixon – 1836

Unfortunately for Mitchell, the sales of his map fell significantly short of reimbursing him, and his dire financial circumstances could only have been exacerbated when two years later, his assistant surveyor Robert Dixon published his own map of the nineteen counties. Dixon had worked closely with Mitchell on the trigonometrical survey that resulted in Mitchell’s map of the nineteen counties. According to Mitchell, Dixon was the only surveyor in his office that Mitchell fully trusted. That was, until Dixon applied for two years leave to return to England, using the voyage home to draw his own map of the nineteen counties with the surveying records he had accumulated as assistant surveyor to Mitchell. Upon arrival in England, he engaged a London map seller to produce and sell the map. Copies sold for two pounds – twice the price of Mitchell’s.

Dixon’s map is considered to have had several advantages over Mitchell’s in terms of its commercial viability. Where Mitchell’s map emphasised the topography of the surveyed land and its scientific credentials, Dixon focussed on the map’s cadastral utility to prospective settlers and was therefore more squarely aimed at prospective settlers. In any event, when Dixon returned to Australia, he was suspended by Mitchell, only to later be reinstated and sent to Moreton Bay.