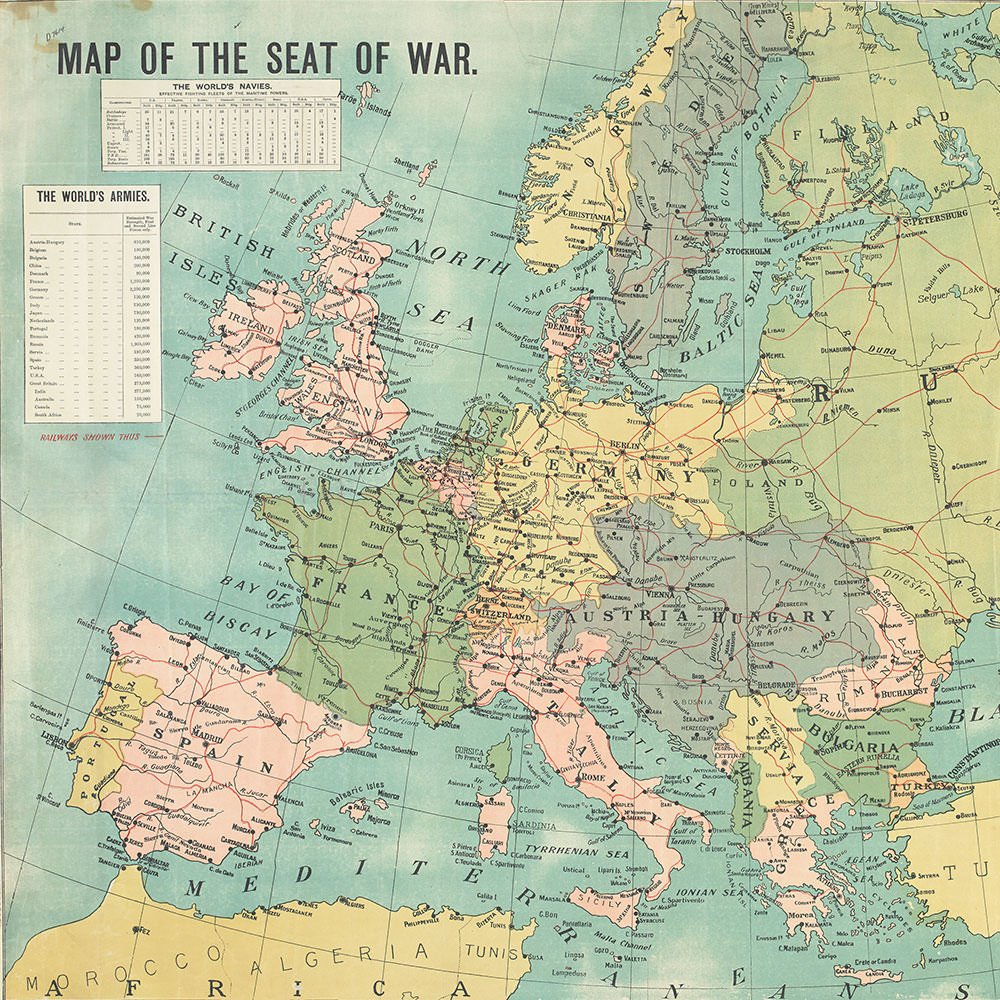

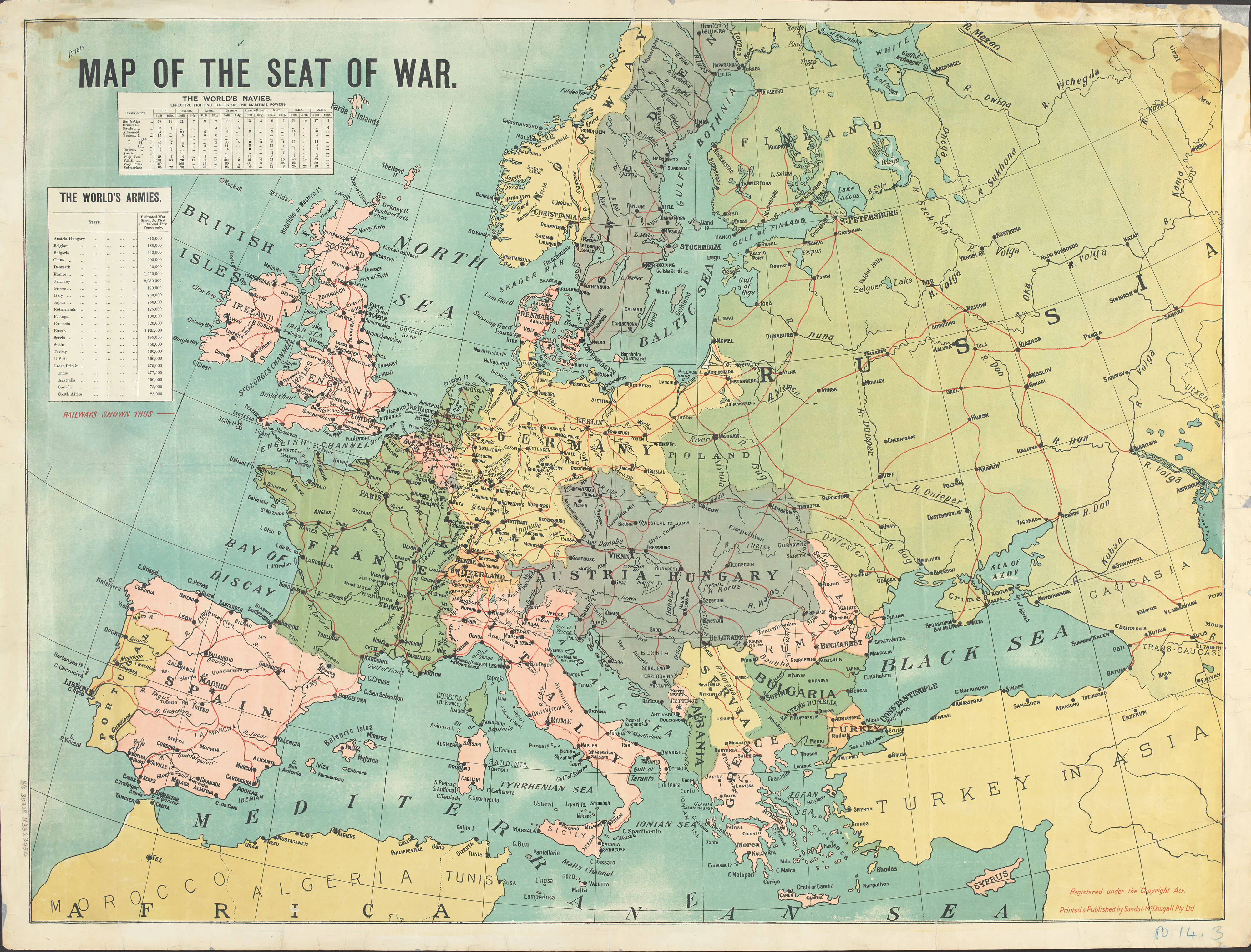

World War I caused unprecedented economic, political and devastation, but it also provided business opportunities. One commercial success story was that of mapmaker Herbert Edward Cooper Robinson. Robinson had formed one of three partners of mapmaking firm Higinbotham, Robinson and Harrison but it was declared bankrupt in April 1888. In 1895, Robinson set up his own map publishing business in Sydney. From almost the moment the first world war was declared, he began supplying war maps to the newspapers. On 10 August 1914, Robinson published his first war map. He had prepared the map using his existing stock, in particular, he used a map he had published in December 1913 for use in schools (‘Robinson school map’).

Sands & McDougall was a Melbourne-based firm of stationers, printers, engravers and booksellers that had formed in the 1850s and was known mainly for its annual directories. Three days before Robinson published his first war map, Sands & McDougall had published its own map. According to the Sands & McDougall retail manager’s evidence, he acquired a copy of the Robinson school map, then later other maps. He used the Robinson school map as it was on the same scale that they wished to produce their own map, but they were obliged to leave out some elements to fit it onto a smaller sheet. On 17 August 1914, Robinson sent a letter of demand to Sands & McDougall, citing copyright infringement of his school map.

A central legal issue was the question of ‘originality’ as applied to maps. In 1912 Australia had adopted the Imperial Copyright Act – a British statute designed to reform copyright law in line with the Berne Convention and bring consistency across Britain’s colonial possessions. This new Act offered protection to ‘original works’. For Robinson to argue that his work was protected by copyright law, he needed to establish that his map was ‘original’. Sands & McDougall argued that the phrase ‘original…work’, appearing in the new Imperial Copyright Act required novelty so striking ‘as to differ substantially from any presentation previously adopted’. The Judge at first instance disagreed so Sands & McDougall appealed to the High Court of Australia. The High Court held that Robinson was the ‘author’ of the ‘original’ work by applying ‘independent, intellectual effort’. Justice Isaacs claimed that ‘in copyright law the two expressions ‘author’ and ‘original work’ have always been correlative: the one connotes the other’. Moreover, it was held that despite some minor improvements by Sands & McDougall, the had reproduced a ‘substantial part’ of Robinson’s map in a ‘material form’.

This is a landmark Australian case which is still cited today. It played a key role in consolidating a particular version of authorship in copyright law – one which emphasised a sole creator – by downplaying the contribution others made to Robinson’s map. This case was ground-breaking because it cemented authorship as the touchstone of copyright law, even in the case of a work characterised as ‘factual’.