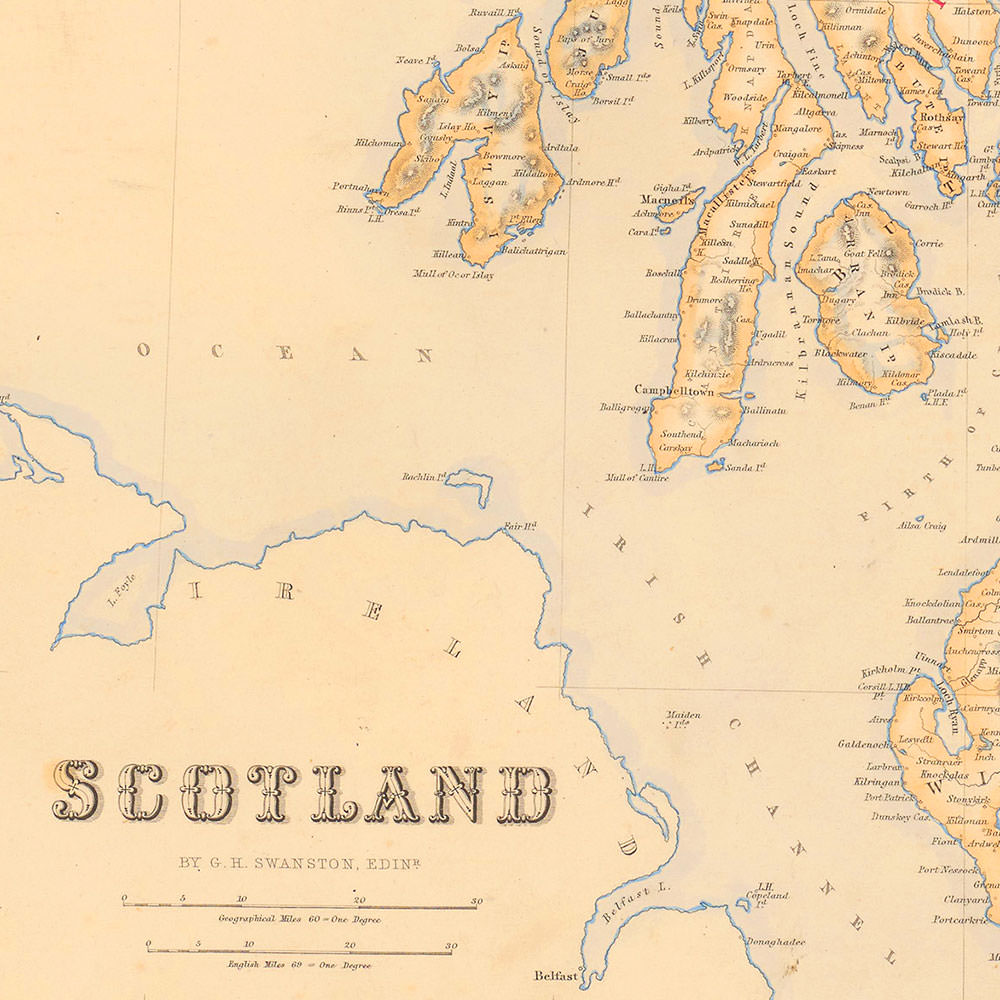

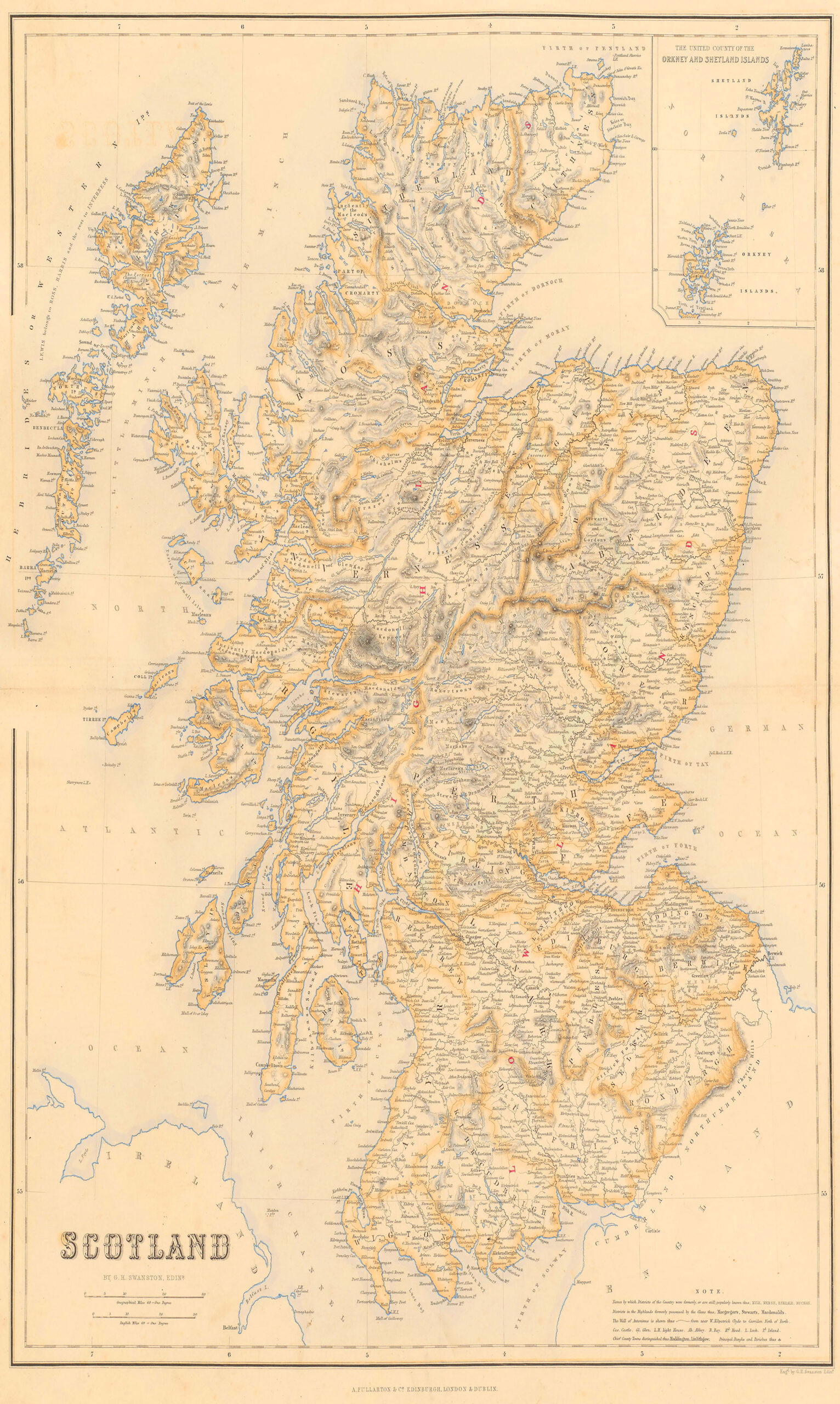

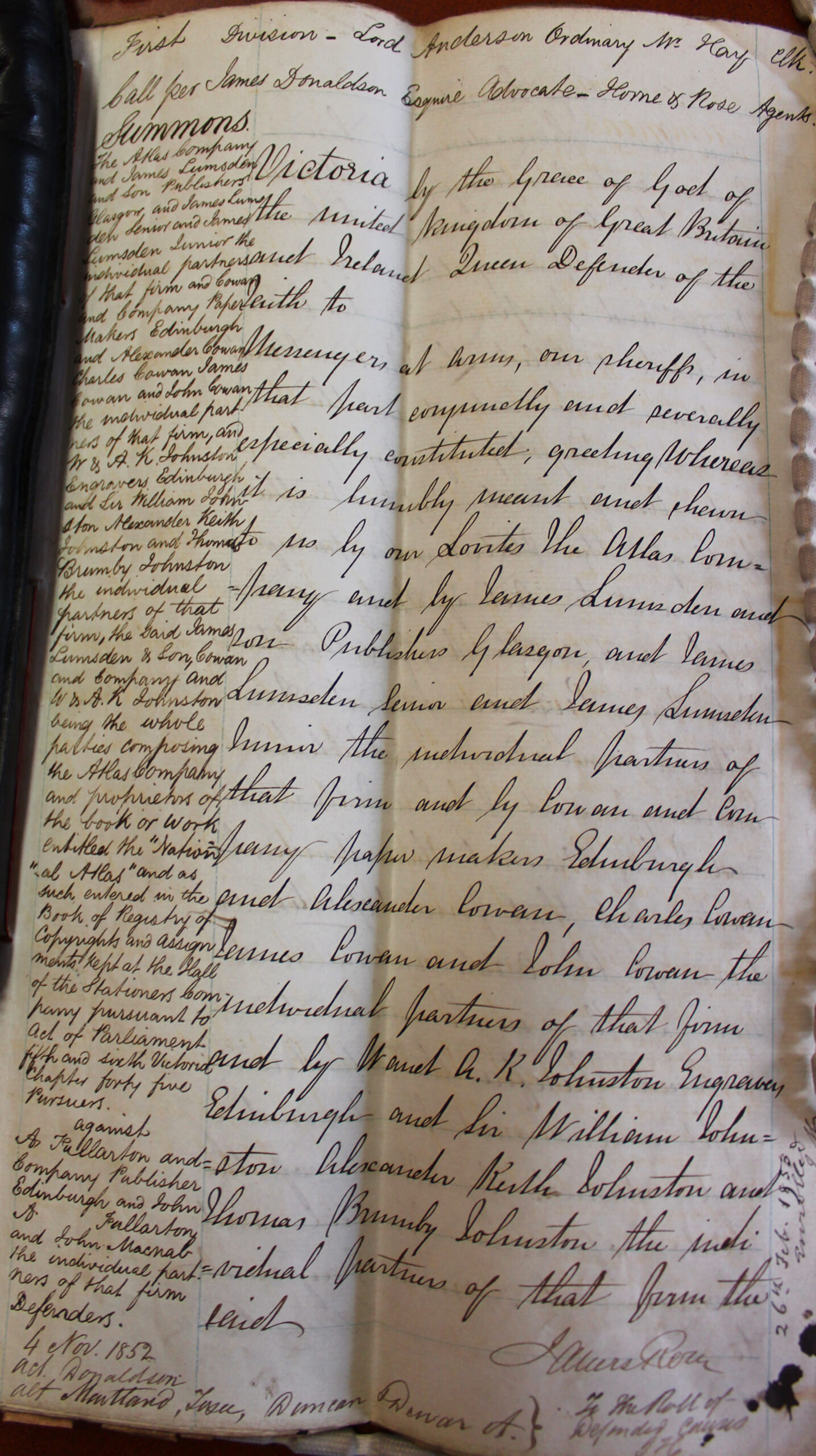

This case was the first to be brought under the new provisions of the Literary Copyright Act 1842, and generated considerable interest among mapmakers and in the press. W & A K Johnston was a prominent Edinburgh publishing house, publishing The National Atlas in 1843. The publishing house and its co-founder Alexander Keith Johnston had invested seven years of his time and £5000 in the Atlas, only to discover it had been copied by rival firm, A Fullarton & Company.

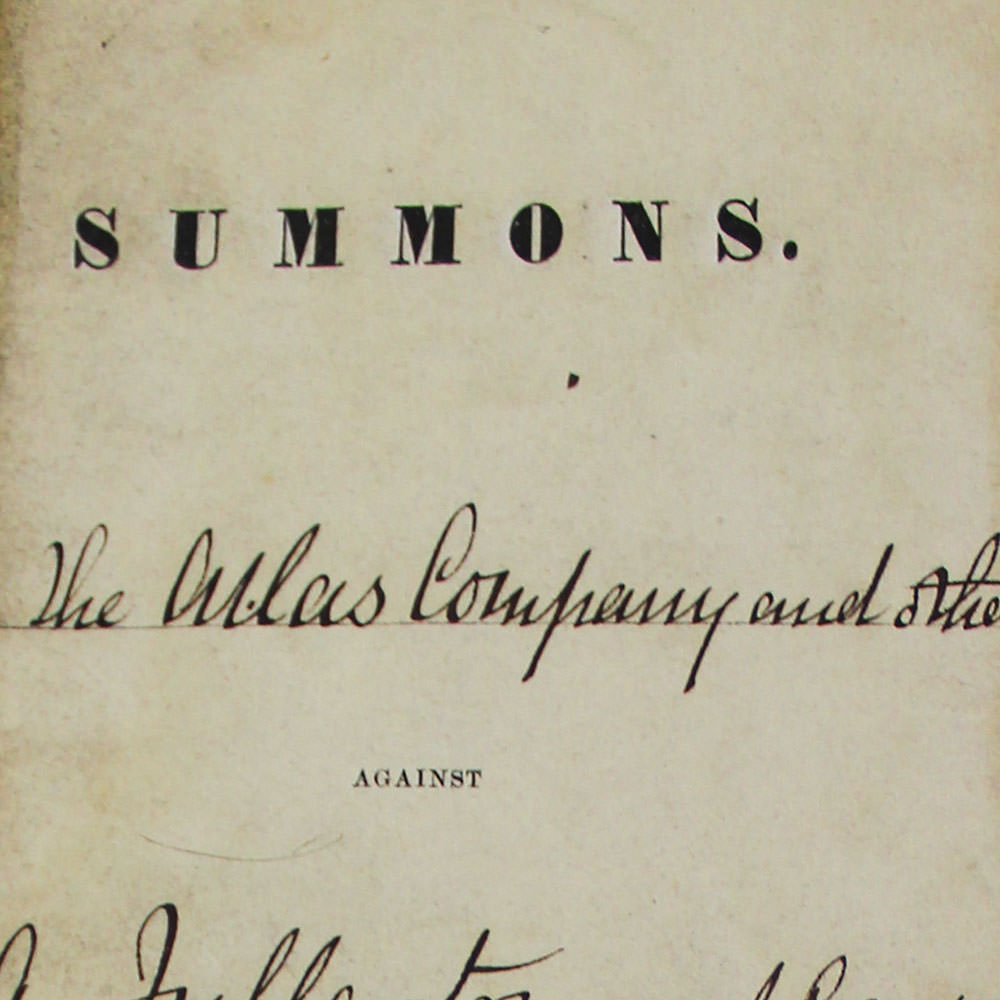

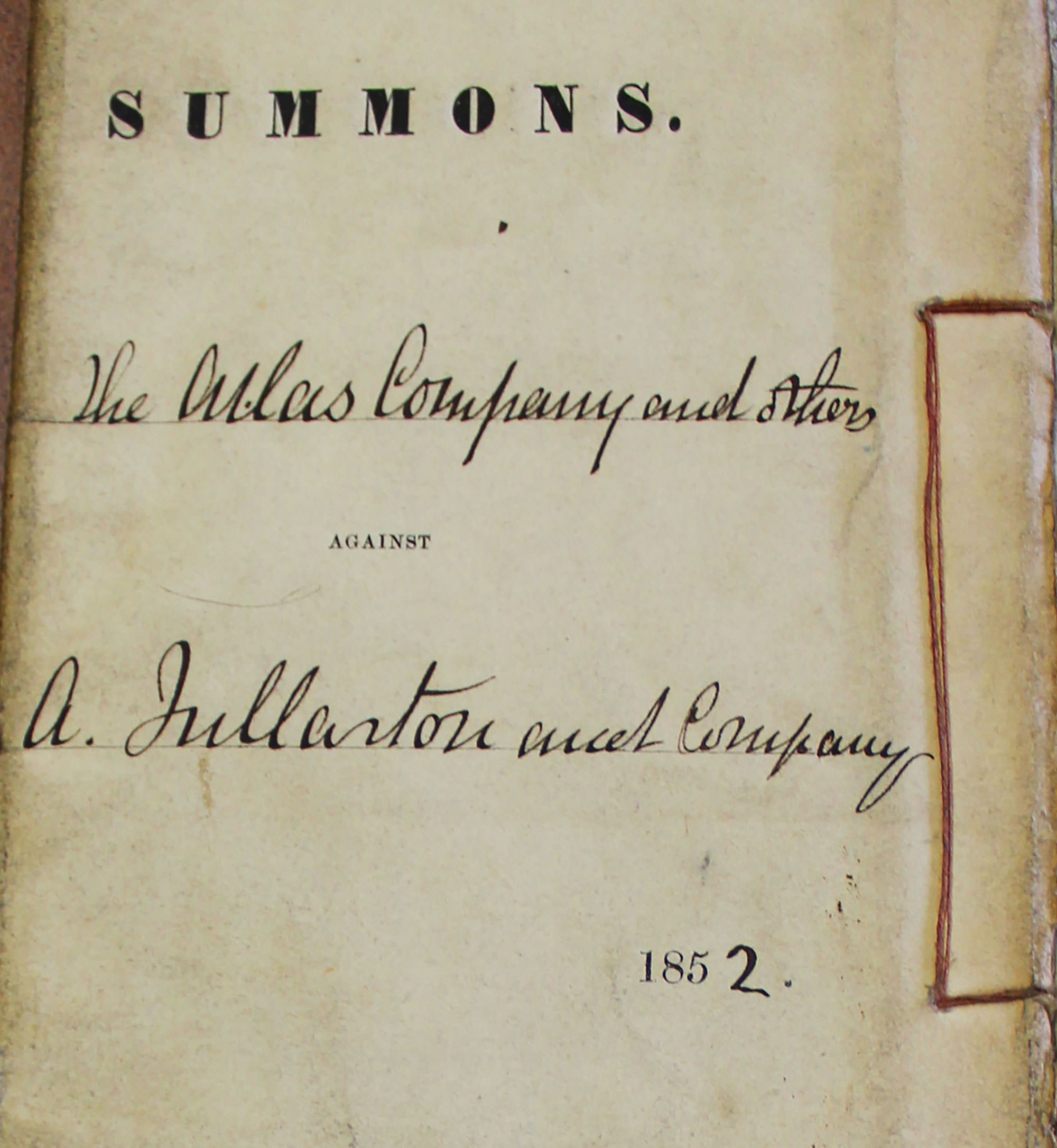

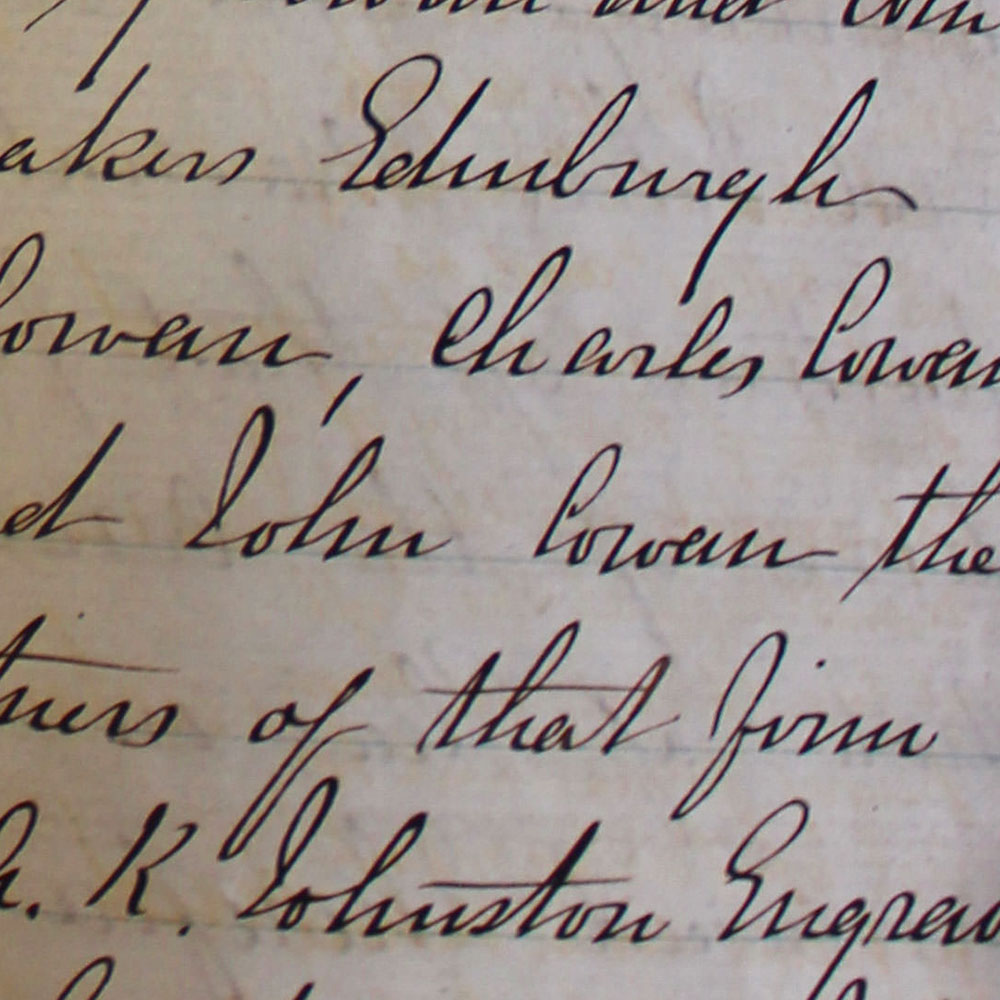

On 25 June 1852, the Pursuers, comprising of the firm W & A K Johnston, its partners and their many collaborators on the National Atlas project, initiated proceedings in the Scottish Court of Session. They argued that the maps appearing in Fullarton’s Companion Atlas were copied from their own, specifically focussing on the maps of Scotland, the world in hemispheres, South America, Europe and North America. At the trial, Keith Johnston emphasised the extraordinary labour and investment involved in creating his maps for the National Atlas and argued that Fullarton’s map of Scotland was ‘a mere mechanical copy’ of his own. Although the scale in Fullarton’s map was reduced, he explained that this variation was easily achieved ‘at a trifling expense’ by using a device known as a pantograph. The Pursuers also claimed that Fullarton was not even copying the most up to date version of the map. New information since the National Atlas’s publication would have allowed for additions and adjustments including the correction of coast lines and the inclusion of new lighthouses that were erected since 1843. Their case was supported by evidence given by draughtsmen, engravers and publishers who attested to the similarity between the sets of maps. Damning evidence was given by an engraver who even witnessed the use of a pantograph to create pencil drawing copies of Johnston’s map.

The central plank of the Defenders’ argument was that the atlases resembled each other because the same geographical sources were used to produce them. Fullarton’s counsel argued that ‘if different maps of the same country are skilfully made, they must agree in their outlines’. It was rather the interior details within a map’s outlines that distinguished it from the Pursuers. A witness for the Defenders, an assistant editor, remarked upon the different mountains, rivers and names that appeared in the Fullarton’s Companion Atlas. The Defenders also sought to distinguish the atlases for their ‘totally different purposes’. Whereas the “National” was an eminently a commercial atlas, the “Companion” was an antiquarian or historical atlas.

Having heard the evidence, the jury returned a verdict for the Pursuers. However, they awarded damages of only £200 – less than half the loss estimated by W & A K Johnston’s witnesses and a fifth of what they had claimed in their original summons. On 30 July 1853 Bartholomew Senior wrote again to his son John, letting him know the trial had ended in a verdict for Johnston and observing ‘which with the Costs will be a heavy blow to Fullarton it being generally thought that £1000 will scarce clear them’ (ACC 1022/BR/11, Bartholomew Snr to Bartholomew Jnr, 20 July 1853, National Library of Scotland).